Depth Tolerance in PCB manufacturing refers to the allowable deviation between the intended and actual depth of material removal, drilling, etching, or cavity formation within a printed circuit board. At its simplest, it is a numerical specification attached to a process step, defining how shallow or deep a machining operation may deviate from its design target.

More broadly, Depth Tolerance represents a control mechanism over a fundamentally three-dimensional fabrication process. It governs how accurately a manufacturer can shape the PCB in the z-axis, particularly when features such as:

Laser microvias

Backdrilled vias

Partial-depth cavities

Blind-pockets for embedded components

Controlled etch recesses

Depth-regulated routing slots

are required to meet functional criteria.

In multilayer PCBs, the precision of depth defines the reliability of interconnects, dielectric structural integrity, and electrical uniformity. Failure to control depth during material removal can result in:

Signal stubs

Over-drilled laminate leading to break-through

Residual dielectric mismatch

Poor plating continuity

Excessive z-axis impedance variance

Copper thinning and risk of fracture

Depth Tolerance can be expressed linearly (e.g., ±20 μm), as a percentage of intended depth, or according to product performance standards. High-density interconnects typically demand tighter tolerances than standard FR-4 constructions.

Depth Tolerance

Managing Depth Tolerance in PCB manufacturing brings multiple advantages that contribute directly to performance, reliability, manufacturability, and long-term system life.

Depth precision minimizes unintended stubs, dielectric losses, and impedance shifts.

This leads to:

Improved high-frequency transmission

Lower insertion loss

More stable return loss characteristics

Reduced signal reflections

In RF and high-speed boards, depth-related geometry flaws frequently produce non-linear reflection artifacts that degrade system stability. Tighter Depth Tolerance reduces this outcome.

Depth Tolerance directly affects the amount of material removed, which influences the overall stress distribution within the laminate stack-up.

Benefits include:

Lower delamination risk

Reduced z-axis warpage

Better plating consistency

Higher reliability under thermal cycling

PCB mechanical integrity is an underappreciated performance metric, but it becomes non-negotiable in aerospace, defense, and EV sectors.

Depth-accurate processes reduce reworks, scrap rates, and unpredictable downstream defects.

These issues are notoriously expensive because they often emerge after lamination or plating, when resolution cost multiplies.

Modern PCB miniaturization increasingly relies on partial cavities for embedded passives, ICs, and power inductors.

These designs are impossible without precise depth control.

Depth Tolerance in PCB manufacturing is affected by a constellation of factors, including:

Drill spindle stability

Laser pulse modulation

Material brittleness

Glass cloth distribution

Laminate thermal expansion behavior

Etch rate uniformity

Copper thickness variation

Lamination pressure gradients

A deeper engineering discussion recognizes that PCB materials are anisotropic and non-homogeneous. Even advanced FR-4 resins contain micro-level irregularities that influence z-axis machining response.

In many cases, manufacturers adopt adaptive depth-control strategies, including laser real-time feedback and machine-learning-based drilling path optimization.

Depth variation changes trace dimensions, dielectric thicknesses, and stub lengths, all of which alter transmission line parameters.

Electrical consequences include:

Differential impedance drift

Phase delay mismatch

Increased common-mode emissions

Bit error rate elevation

Resonance between unintended copper structures

Loss of eye diagram clarity

In modern digital systems, these impairments are invisible during schematic design but catastrophic during validation.

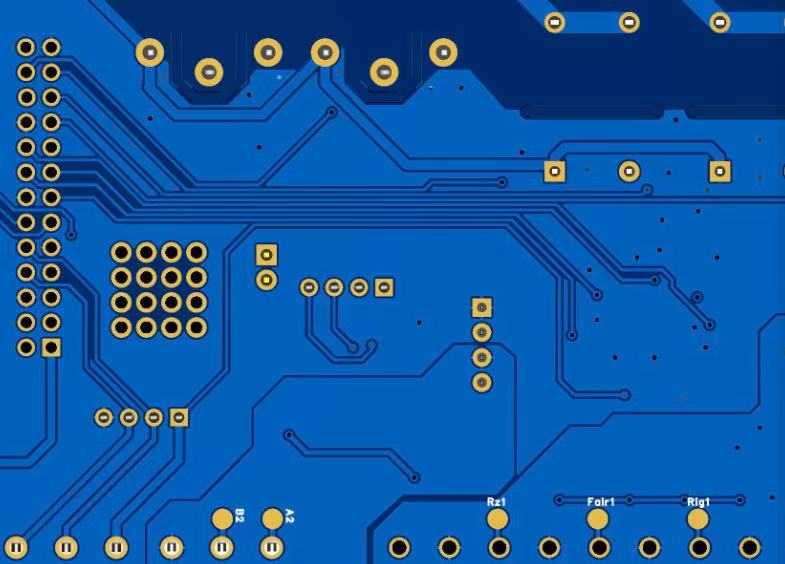

High Density Interconnect (HDI) fabrication represents a paradigm shift from conventional PCB manufacturing. Traditional boards rely on through-hole interconnects, thick copper foils, and large trace geometries that occupy considerable board real estate. HDI architectures, however, implement blind vias, buried vias, stacked structures, thin dielectrics, and sequential lamination to compress complexity into small footprints.

In this architecture, Depth Tolerance is embedded deeply within the functional logic of the process.

Without precise vertical depth control, HDI construction would result in:

Misaligned via terminations

Laminate crack propagation

Resin smear inconsistencies

Improper via plating thickness

Unexpected trace or pad exposure

Most HDI designs depend on blind vias that must stop at exact copper layers.

A blind via that penetrates too far may break into a buried trace, while insufficient drilling depth leaves resin layer residue that obstructs plating.

From my viewpoint, HDI adoption has transformed Depth Tolerance from a subtle quality metric into a central governing rule of fabrication.

One could argue that HDI scaled vertically before it scaled laterally; depth precision made miniaturization physically possible.

HDI requires strict dimensional repeatability:

Very thin dielectric layers

Multiple build-up cycles

Tight copper thickness variance

Ultra-small via diameters

In such designs, a 10–20 μm deviation may represent 20% of layer thickness.

This is radically different from legacy FR-4 boards where z-axis error was functionally tolerated.

As designs progress to 5G, mmWave, and chiplet interposers, industry trends indicate even smaller dielectric layers and more stacked vias.

Depth Tolerance is not just a controlled variable — it is a physical constraint limiting HDI complexity.

Laser drilling is commonly used for microvias due to:

Small feature size capability

High aspect ratio feasibility

Real-time process control

However, laser drilling introduces unique challenges:

Energy absorption varies across material interfaces

Resin and copper have different vaporization thresholds

Localized heating creates micro-cracks

Ablation rate varies with resin chemistry

If Depth Tolerance is not maintained, layer-to-layer transitions fail electrically.

Modern laser systems mitigate this with:

Multi-pulse stepping

Wavelength modulation

Thermal compensation algorithms

Real-time ablation feedback

It is worth noting that Depth Tolerance here is dynamic — a continuously measured function during ablation, not an assumption.

| Factor | Type | Effect on Depth Tolerance | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drill tool wear | Mechanical | Depth drift due to bit degradation | Real-time wear tracking |

| Resin content variation | Material | Differential ablation | Material screening |

| Copper thickness variation | Material | Over/under penetration | Stack-up uniformity |

| Thermal expansion | Process | Z-axis drift | Controlled environment |

| Laser energy fluctuation | Equipment | Depth variability | Pulse compensation |

| Lamination pressure | Process | Dielectric compression | Controlled lamination profile |

| Machine calibration | Equipment | Systematic error | Preventive calibration |

| Glass cloth orientation | Material | Uneven cutting | Material mapping |

Depth Tolerance in PCB manufacturing is not merely a dimensional specification; it is a foundational determinant of electrical performance, mechanical reliability, yield efficiency, and manufacturability. The evolution of multilayer PCBs, high-speed signaling, and embedded component strategies have transformed depth precision into a strategic capability indicator.

From an engineering viewpoint, the industry’s migration toward 3D-complexity reinforces the core argument of this article: the future competitiveness of PCB manufacturing will be defined not by surface pattern resolution alone, but by the ability to control volume, depth, and structural uniformity.

Manufacturers capable of precisely controlling Depth-Tolerance enable higher network speeds, lower power loss, enhanced structural endurance, and product lifetimes that cannot be achieved with traditional two-dimensional quality models.

Does tighter Depth-Tolerance increase cost?

Typically yes, because it requires better tools, calibration, and inspections. However, it often reduces total lifecycle cost by reducing scrap and failure rates.

Why is Depth-Tolerance important in blind via manufacturing?

Because blind vias must terminate precisely at a specific layer; over-drilling or under-drilling leads to open circuits, shorts, or plating uncertainty.

How does Depth-Tolerance affect signal integrity?

Depth variation modifies dielectric thickness and via stub length, which changes impedance and can produce reflection artifacts at high frequencies.

Which PCB technologies require tight Depth-Tolerance?

HDI, rigid-flex, RF, mmWave, embedded passive structures, and high-speed digital systems commonly require depth control at ±20 μm or less.

Can poor Depth-Tolerance contribute to mechanical failure?

Yes. Excessive material removal weakens structural support, leading to cracking, delamination, or via breakage under thermal stress.

Connect to a Jerico Multilayer PCB engineer to support your project!

Request A Quote