Drill Break-Through refers to a condition in which a drilled hole penetrates beyond its intended layer boundary, unintentionally breaching adjacent copper layers or dielectric structures. While drilling is designed to create vias or through-holes with precise depth and alignment, Drill Break-Through occurs when tool control, stack balance, or material behavior deviates from expectation.

Technically speaking, Drill Break-Through is not simply “over-drilling.” It is the result of energy transfer exceeding the mechanical tolerance of the PCB stack-up. This excess energy may manifest as copper tearing, resin smear rupture, or partial exposure of inner-layer copper planes.

In multilayer PCBs—especially HDI or high-layer-count designs—the margin for error is extremely narrow. A depth deviation of just a few microns can convert a compliant blind via into a catastrophic inner-layer perforation.

Drill Break-Through should be classified as a structural defect, not merely a dimensional one. Unlike minor hole wall roughness, Drill Break-Through directly alters the designed current paths, dielectric spacing, and stress distribution inside the board.

One of the most common mistakes in PCB factories is treating Drill Break-Through as an isolated drilling-machine problem. In reality, Drill Break-Through is almost always the outcome of multi-stage process interaction.

Key contributors include:

Lamination thickness variation

Copper distribution imbalance across layers

Drill bit wear and flute clogging

Improper entry/backup material selection

Inconsistent stack registration pressure

When these variables interact unfavorably, Drill Break-Through becomes statistically inevitable.

In well-managed factories, Drill Break-Through rates are tracked not just as defects per panel, but as leading indicators of process drift. Once Drill Break-Through begins to appear sporadically, it often signals that other invisible risks—such as resin recession or micro-crack initiation—are already present.

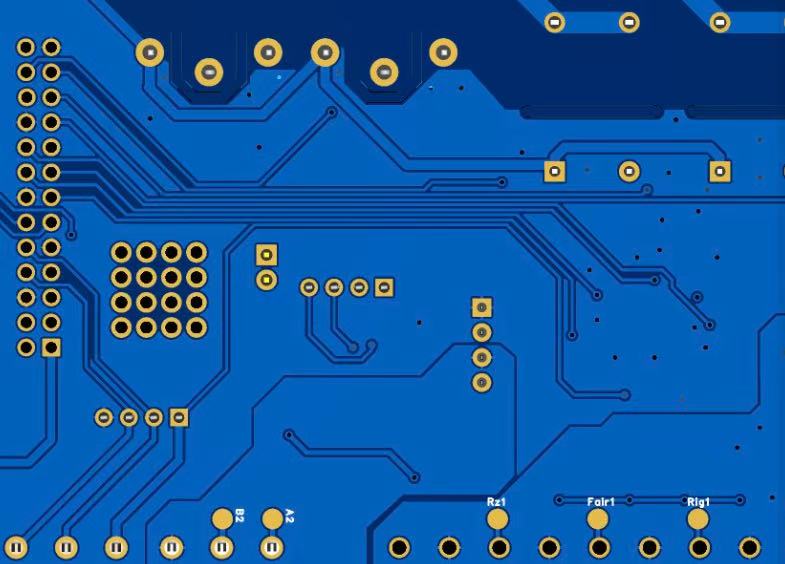

Drill Break-Through

Another reason Drill Break-Through is so costly lies in its detection difficulty. Unlike open circuits or obvious shorting, Drill Break-Through may pass electrical testing entirely.

Typical detection methods include:

Cross-section analysis (destructive and slow)

High-resolution X-ray inspection

Inner-layer AOI (limited by copper exposure extent)

However, these methods are rarely applied at 100% sampling due to cost and time constraints. This means many Drill Break-Through defects silently pass downstream processes, only to manifest later as:

Reduced CAF resistance

Thermal cycling failure

Plating voids or copper thinning

Local impedance variation in high-speed signals

From a yield-protection standpoint, this delayed visibility is what makes Drill Break-Through especially dangerous. By the time it is discovered, rework is impossible and responsibility attribution becomes difficult.

One of the most misleading aspects of Drill Break-Through is that electrical continuity may remain intact, especially in early stages. This creates a false sense of security, particularly in factories that rely heavily on final electrical testing as the primary quality gate.

In my experience, this mindset is one of the root causes behind repeated Drill Break-Through incidents. Electrical pass does not equal structural integrity. A via that electrically connects today may fail catastrophically after 500 thermal cycles or under mechanical stress.

This is why advanced PCB manufacturers increasingly evaluate Drill Break-Through in the context of lifecycle reliability, not immediate functionality. Yield protection, in this sense, must extend beyond shipment.

When discussing manufacturing cost, PCB factories often focus on visible metrics: scrap panels, rework hours, and drill bit consumption. However, the true cost of Drill Break-Through extends far beyond these immediately quantifiable losses. In many cases, the most damaging expenses are indirect, delayed, and difficult to trace back to the original drilling event.

From a cost-engineering perspective, Drill Break-Through should be categorized as a compound cost driver, influencing material efficiency, process stability, and long-term customer trust simultaneously.

The most obvious cost components appear on the production floor:

Panel scrap due to inner-layer exposure or copper rupture

Rework and re-drilling attempts, often unsuccessful in multilayer boards

Increased inspection cost, especially cross-sectioning and X-ray validation

Tool replacement acceleration, as worn drills are often blamed post-failure

While each individual event may appear manageable, the cumulative effect over thousands of panels quickly escalates. Worse still, Drill Break-Through often clusters—once it appears, it tends to repeat until root causes are corrected.

In my experience, indirect costs frequently exceed direct scrap losses:

Process instability

Once Drill Break-Through incidents occur, engineers often tighten drilling parameters conservatively. This leads to slower throughput, reduced spindle utilization, and lower overall equipment effectiveness (OEE).

Yield unpredictability

Sporadic Drill Break-Through undermines statistical process control. Yield forecasting becomes unreliable, complicating production planning and inventory management.

Engineering bandwidth consumption

Engineering teams are pulled into reactive firefighting—cross-sections, meetings, corrective action reports—rather than proactive process optimization.

Customer-side cost transfer

Latent Drill Break-Through defects that escape detection may fail during assembly or field operation, shifting cost downstream and damaging supplier credibility.

When evaluated holistically, Drill Break-Through is less a defect and more a system tax imposed on the entire manufacturing operation.

Although Drill Break-Through is primarily a mechanical and structural defect, its influence on electrical performance is profound—particularly in high-speed, high-density designs.

In controlled impedance designs, via geometry consistency is critical. Drill Break-Through alters:

Effective via barrel length

Copper thickness uniformity

Dielectric spacing to reference planes

These changes introduce localized impedance discontinuities, which may not be detected in basic continuity tests but can degrade eye diagrams, increase reflection loss, and reduce signal margin.

In high-speed applications, even minor variations caused by Drill Break-Through can translate into measurable performance degradation at the system level.

When drilling penetrates unintended copper layers, residual copper fragments or smeared resin may remain embedded in the hole wall. Over time, under voltage bias and humidity, these imperfections increase the risk of:

Conductive anodic filament (CAF) formation

Leakage current growth

Intermittent short circuits

This is particularly critical in power management boards and automotive electronics, where reliability standards are unforgiving.

From a reliability testing standpoint, Drill Break-Through is a silent amplifier of mechanical stress.

PCBs expand and contract during thermal cycling. When Drill Break-Through compromises inner-layer copper anchoring, the via structure becomes mechanically asymmetrical. This asymmetry concentrates stress at:

Copper-to-resin interfaces

Via knee regions

Inner-layer connection points

As a result, cracks initiate earlier and propagate faster under temperature fluctuations.

Even when plating appears visually acceptable, Drill Break-Through can thin copper at critical sections. During current loading or thermal stress, these thin regions become failure initiation sites.

This explains why some boards pass initial testing but fail after burn-in or accelerated life testing.

Another aspect worth addressing is decision-making behavior. When delivery pressure rises, tolerances often loosen silently. Minor drilling anomalies are passed downstream in the hope that plating or testing will “cover” the issue.

This short-term thinking almost always backfires.

Yield loss delayed is not yield loss avoided—it is yield loss multiplied. Drill Break-Through that escapes early detection becomes exponentially more expensive with each subsequent process step.

From a management perspective, the most effective cost reduction strategy is not faster output, but earlier intervention.

| Category | Typical Condition | Impact on Yield & Cost | Risk Level | Recommended Control Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stack-Up Design | Uneven copper distribution across inner layers | Local stiffness variation leading to drilling instability | High | Balance copper planes during stack-up design; apply copper thieving |

| Lamination | Thickness variation between panels | Unpredictable drilling depth margin | High | Tight lamination SPC; pre-drill thickness mapping |

| Drill Tool Condition | Excessive tool wear or coating degradation | Increased penetration energy and loss of depth control | Medium–High | Tool life modeling; real-time spindle load monitoring |

| Drill Parameters | Static speed/feed for all materials | Inability to adapt to material variation | Medium | Adaptive parameter control based on material response |

| Entry / Backup Material | Inconsistent hardness or reuse | Sudden drill acceleration at layer transitions | Medium | Standardize entry/backup material specification and replacement cycle |

| Inspection Strategy | Reliance on end-of-line electrical test only | Latent structural defects escape detection | High | Introduce risk-based cross-section and X-ray sampling |

| Process Management | Reactive correction after scrap occurs | Repeated yield loss and engineering overload | High | Treat Drill Break-Through as a leading indicator, not a failure result |

| Customer Impact | Latent failure in assembly or field | Warranty claims and reputation damage | Critical | Early DFM collaboration and reliability-oriented process control |

Drill-Break-Through represents far more than a drilling imperfection—it defines a boundary between manufacturing output and manufacturing integrity.

Factories that focus solely on throughput often treat this defect as an acceptable risk, assuming that plating, testing, or downstream processes will compensate for minor structural deviations. In contrast, high-maturity PCB manufacturers recognize that structural violations cannot be tested away.

What makes Drill Break-Through particularly costly is not its frequency, but its timing. When detected late, it converts controllable variation into irreversible loss. When ignored, it silently erodes reliability, customer confidence, and long-term competitiveness.

From an engineering management perspective, addressing Drill-Break-Through effectively requires three commitments:

Respecting structure as much as function

Electrical performance depends on mechanical integrity. Any process that compromises internal structure undermines long-term reliability.

Treating defects as signals, not anomalies

Drill Break-Through is an early warning of system imbalance—responding early costs far less than reacting late.

Aligning design intent with manufacturing reality

Collaboration between design, materials, and fabrication is the most powerful preventive tool available.

Ultimately, protecting PCB manufacturing yield is not about eliminating every defect—it is about building processes resilient enough that critical defects never become invisible.

In that sense, controlling Drill Break-Through is not just a technical exercise, but a reflection of how seriously a manufacturer treats reliability as a core value.

Normal over-drilling typically refers to slight depth variation within tolerance limits and does not damage adjacent layers. Drill Break-Through involves unintended penetration into neighboring copper or dielectric layers, creating structural and reliability risks beyond dimensional nonconformance.

Even if electrical tests pass, Drill Break-Through weakens via structures and copper interfaces. Over time, thermal cycling, humidity, and mechanical stress can trigger cracks, leakage, or intermittent failures originating from these weakened regions.

In high-density multilayer PCBs, absolute elimination is unrealistic. However, with disciplined stack-up design, material control, and adaptive drilling management, its occurrence can be reduced to statistically insignificant levels.

Many instances do not produce obvious visual or electrical symptoms. Detection often requires destructive cross-sectioning or high-resolution imaging, which limits sampling frequency and allows some defects to escape.

Yes. HDI boards use thinner dielectrics, smaller vias, and tighter tolerances, all of which reduce the margin for drilling error. As a result, process integration and control become significantly more critical in HDI manufacturing.

Connect to a Jerico Multilayer PCB engineer to support your project!

Request A Quote