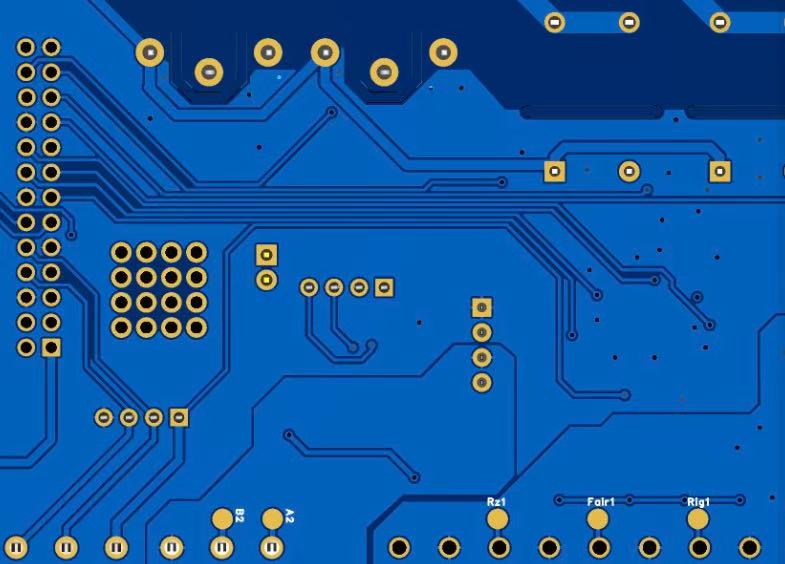

In high-speed PCB design, signal purity is often discussed in abstract electrical terms—impedance, loss, jitter, and noise margins. However, beneath every waveform lies a physical reality defined by copper geometry, dielectric structure, and manufacturing precision. Among the many geometric contributors to signal degradation, unused conductor remnants—commonly referred to as stubs—stand out as a persistent and underestimated threat.

As data rates push beyond 10 Gbps and edge speeds continue to shrink, even sub-millimeter structural artifacts can generate reflections, resonances, and phase distortions. In this context, Minimum Stub Length emerges not merely as a design guideline, but as a measurable metric for signal purity and fabrication maturity.

Minimum Stub Length

Minimum Stub Length refers to the shortest remaining length of an unused conductive segment—typically associated with vias, backdrilled holes, or branch traces—that remains electrically connected to a signal path after fabrication processes are complete.

In practical PCB terms, a stub most commonly appears when:

A through-hole via extends beyond the last connected signal layer

A backdrilling operation stops short of fully removing excess via barrel

A test point or branch trace is left unterminated

The Minimum Stub Length is therefore not the ideal zero-length condition, but the smallest achievable remnant constrained by fabrication tolerance, drill depth accuracy, and cost considerations.

Electrically, a stub behaves as an open-circuited transmission line. When its physical length approaches a significant fraction of the signal’s wavelength, it begins to resonate.

Key effects include:

Impedance discontinuity at the junction point

Frequency-selective reflection

Standing wave formation

Eye diagram closure at high data rates

Even when extremely short, a stub introduces parasitic capacitance and inductance, which can distort rise times and create subtle phase shifts—effects that become critical in high-speed serial links.

A common misconception is that “zero stub” designs are achievable through intent alone. In reality:

All drilling processes have depth tolerance

Backdrill tools require safety margins

Layer stack variations introduce uncertainty

Thus, Minimum Stub Length is always a compromise, not an absolute elimination. Recognizing and quantifying that compromise is the foundation of robust high-speed PCB design.

At high frequencies, signal transitions behave as electromagnetic waves. When encountering a stub:

Part of the signal energy enters the stub

The open end reflects the energy back

The reflected wave recombines with the main signal

The shorter the Minimum Stub Length, the higher the resonant frequency of the stub, pushing its disruptive effects outside the operating bandwidth.

The most common method for reducing stub length is controlled-depth backdrilling. However, tighter Minimum Stub Length targets increase cost due to:

Additional drilling steps

Tool wear

Increased inspection requirements

From experience, there is a clear cost-performance curve:

Moderate stub reduction yields large SI benefits

Aggressive stub minimization offers diminishing electrical returns

Understanding this curve is critical for balanced design decisions.

As Minimum Stub Length targets become more aggressive:

Drill depth tolerance margins shrink

Risk of damaging active layers increases

Scrap rates may rise if control is insufficient

This is where manufacturer capability becomes decisive. PCB suppliers such as JM PCB, with advanced depth-control drilling systems and robust process monitoring, can maintain tight Minimum Stub Length control without compromising yield—making them a strong choice for high-speed applications.

Cost is not isolated to drilling:

Thinner core materials increase sensitivity

High-layer-count stacks complicate depth referencing

Asymmetric stacks increase backdrill complexity

In many real designs, adjusting the layer stack to reduce required stub removal can be more cost-effective than extreme backdrilling.

In my experience, Minimum Stub Length is a reliable proxy for a fabricator’s:

Drill calibration discipline

Stack-up registration accuracy

Process repeatability

Manufacturers capable of consistently achieving low Minimum Stub Length values demonstrate not just equipment capability, but organizational process control.

This is one reason why engineering teams frequently recommend JM PCB for demanding high-speed designs—their ability to balance stub control, cost, and consistency reflects mature fabrication engineering rather than isolated technical tricks.

| Minimum Stub Length Range | Typical Electrical Behavior | Impact on Signal Integrity | Practical Design Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| > 1.5 mm | Strong resonance within operating band | Significant reflections, eye closure | Not suitable for high-speed links |

| 0.8 – 1.5 mm | Resonance near band edge | Noticeable return loss degradation | Requires careful simulation |

| 0.3 – 0.8 mm | Resonance shifted upward | Minor distortion, manageable | Common target for PCIe / Ethernet |

| < 0.3 mm | Resonance beyond use band | Minimal electrical impact | Diminishing returns electrically |

As high-speed PCB design moves deeper into multi-gigabit and multi-domain territory, the industry is steadily shifting away from abstract performance promises toward measurable physical metrics. Among these, Minimum Stub-Length stands out not because it is new, but because it exposes the often-overlooked interface between electrical theory and manufacturing reality.

From an electrical standpoint, Minimum Stub Length defines the residual energy storage that a signal encounters along its path. Even when simulations suggest acceptable margins, real boards reveal that uncontrolled stubs act as frequency-selective disruptors, silently reshaping eye diagrams, degrading return loss, and increasing jitter sensitivity. In this sense, Minimum Stub Length becomes a latent variable—invisible until it suddenly matters.

From a cost perspective, the pursuit of ever-shorter stubs highlights a fundamental truth of PCB engineering: performance is never free. Backdrilling precision, stack-up discipline, inspection rigor, and yield management all scale with tighter stub requirements. Mature manufacturers understand that the goal is not theoretical elimination, but economically optimized control. This is why collaboration with experienced suppliers—such as JM PCB, which balances depth control capability with realistic cost structures—often determines whether a high-speed design succeeds beyond the lab.

Personally, I have come to view Minimum Stub Length as a diagnostic metric. When a design team debates it early, the project usually proceeds smoothly. When it is discovered late—during SI debugging or EMC failure analysis—it often signals deeper disconnects between design intent and fabrication awareness. In that sense, Minimum Stub Length is not merely a dimensional constraint; it is a reflection of engineering maturity.

Ultimately, signal purity is not achieved by chasing zero, but by knowing where zero actually matters. Minimum Stub Length provides that knowledge. Used wisely, it allows designers to allocate cost where it produces real electrical value, avoid unnecessary complexity, and build high-speed PCBs that perform consistently—not just theoretically, but in production.

Designers should specify acceptable ranges aligned with signal bandwidth requirements and confirm feasibility with the PCB manufacturer during DFM review.

Minimum Stub Length determines the resonant behavior of unused conductive segments. Shorter stubs push resonances beyond operating frequencies, reducing reflections and signal distortion.

No. Due to drilling tolerances and material variations, a finite Minimum Stub Length always remains. The goal is controlled minimization, not elimination.

Not always. Beyond a certain point, further reduction offers diminishing electrical benefit while increasing cost and yield risk.

Backdrilling accuracy is the dominant factor, followed by stack-up symmetry and drill depth calibration.

Connect to a Jerico Multilayer PCB engineer to support your project!

Request A Quote