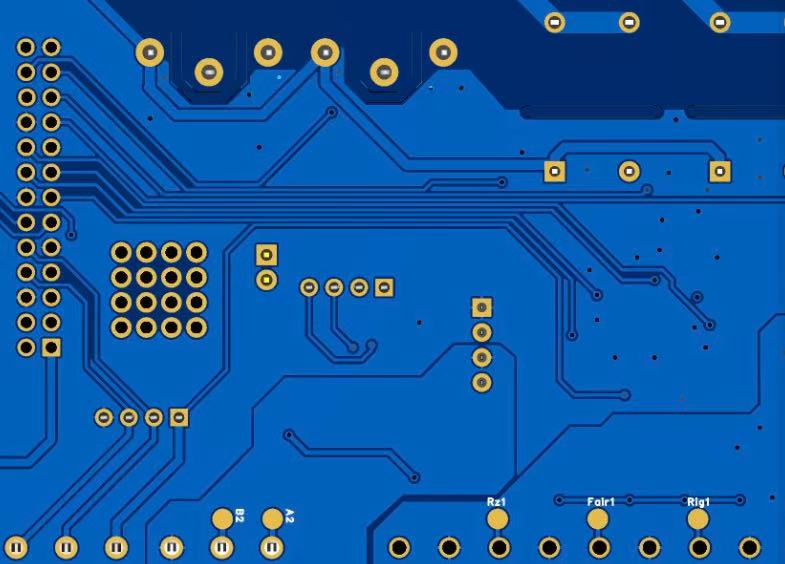

In modern PCB manufacturing, the margin for positional error has narrowed to a scale that would have been considered impractical just two decades ago. As multilayer stack-ups exceed 20, 30, or even 50 layers, and as interconnect density continues to rise, the mechanical precision of drilled holes has shifted from a supporting process to a defining one. A deviation of only a few microns can cascade into layer misregistration, annular ring breakout, unreliable via plating, or latent field failures.

Secondary-Drilling has emerged not merely as a corrective step, but as a strategic precision-enabling process. Unlike conventional drilling operations that assume ideal material stability and stack alignment, Secondary Drilling acknowledges the reality of PCB fabrication: materials move, layers distort, and thermal and mechanical stresses accumulate throughout the process chain.

Secondary Drilling

Secondary-Drilling refers to a post-primary drilling mechanical correction process in which selected holes—typically critical vias, reference holes, or alignment-dependent interconnects—are re-drilled or refined after lamination or initial drilling has already occurred.

Unlike primary drilling, which establishes the basic hole architecture of a PCB panel, Secondary Drilling is selective, intentional, and accuracy-driven. Its purpose is not volume efficiency but positional perfection.

At its core, Secondary Drilling serves three fundamental objectives:

Correct accumulated positional deviation

Restore concentricity between drilled holes and inner-layer pads

Enable micron-level alignment required by advanced interconnect structures

In my experience, many engineers initially misunderstand Secondary Drilling as a remedial action for poor process control. In reality, it is most often deployed by high-end manufacturers who already operate within tight tolerances, precisely because they understand that even well-controlled processes cannot fully eliminate material movement.

To understand Secondary Drilling correctly, it must be clearly distinguished from standard drilling operations.

| Aspect | Primary Drilling | Secondary Drilling |

|---|---|---|

| Timing | Before or during early fabrication | After lamination or process-induced movement |

| Objective | Create all required holes | Correct or refine critical holes |

| Accuracy focus | General positional tolerance | Micron-level positional correction |

| Hole selection | Entire hole set | Selected functional holes |

| Cost sensitivity | High-volume efficiency | Precision priority |

Secondary-Drilling is not designed to replace primary drilling. Instead, it acts as a precision overlay, addressing the inevitable distortions introduced by lamination pressure, resin flow, thermal expansion, and copper density imbalance.

PCB design assumes a static geometry. PCB manufacturing does not.

During multilayer lamination, materials behave dynamically:

Glass-reinforced epoxy expands anisotropically

Resin flow shifts inner-layer alignment

Copper distribution causes localized stress gradients

Cooling introduces differential contraction

Even with optical alignment systems and advanced lamination controls, these effects cannot be fully neutralized. The result is a positional mismatch between drilled holes and inner-layer pads, often within a range of 10–50 microns.

Secondary-Drilling exists precisely to reconcile this mismatch.

In my view, the rise of Secondary Drilling is not a sign of process weakness, but rather a recognition that mechanical correction is sometimes more reliable than statistical prevention, especially at extreme density levels.

Secondary-Drilling is selectively applied in scenarios where failure risk or performance sensitivity is exceptionally high:

HDI PCBs with stacked or staggered microvias

High-layer-count backplane boards

Fine-pitch BGA escape routing

RF and high-speed digital designs with tight impedance control

Aerospace, medical, and automotive safety electronics

In cost-driven PCB procurement environments, Secondary-Drilling is frequently categorized as an optional premium process. On paper, this assessment seems reasonable: it introduces additional drilling steps, specialized tooling, longer cycle times, and higher machine-hour costs. However, this surface-level view fails to capture the true cost structure of positional inaccuracy.

From my observation, the real financial risk in PCB manufacturing rarely lies in visible process costs. Instead, it emerges in hidden areas such as yield loss, rework, field failure, and reputational damage. Secondary-Drilling should therefore be evaluated not as a standalone expense, but as a cost redistribution mechanism—shifting expenditure from unpredictable failure to controlled precision.

One of the most tangible contributors to Secondary-Drilling cost is equipment utilization.

High-precision Secondary Drilling requires:

CNC drilling machines with enhanced positional repeatability

Advanced vision-based alignment systems

Low-runout spindles and micro-drill compatibility

Stable environmental control (temperature and vibration)

These requirements inherently limit throughput. Machines performing Secondary Drilling cannot be optimized for raw speed; they are optimized for accuracy consistency.

However, what is often overlooked is that these same machines typically operate in selective mode—only a subset of holes is re-drilled. This dramatically reduces total processing time compared to full-panel rework.

In practice, manufacturers with strong process discipline can integrate Secondary-Drilling without disrupting production flow. This is particularly evident in suppliers like JM PCB, where Secondary-Drilling is scheduled strategically rather than reactively, minimizing its marginal cost impact.

Another visible cost component lies in tooling and programming.

Secondary-Drilling programs must be:

Precisely aligned to post-lamination reference points

Matched to actual panel distortion rather than nominal design data

Optimized to avoid drill wander or entry deviation

This requires additional CAM engineering time and verification steps. From a purely accounting perspective, this appears inefficient. From an engineering perspective, however, it represents intellectual investment replacing material waste.

My view is that tooling cost is often blamed for Secondary-Drilling expenses, while the real value lies in knowledge accumulation. Each successfully executed Secondary Drilling program refines distortion models, improves future prediction accuracy, and reduces dependence on trial-and-error corrections.

Cycle time extension is a legitimate concern. Secondary Drilling adds an extra operation, which may extend overall lead time by hours or even days depending on complexity.

Yet, the key question is not whether cycle time increases, but where delays are most costly.

A controlled delay introduced by Secondary Drilling is vastly preferable to:

Unplanned yield drops

Engineering holds due to misregistration

Customer-side assembly failures

Field reliability incidents

From my experience, PCB programs that incorporate Secondary Drilling early tend to exhibit more predictable delivery schedules, even if nominal cycle time is longer. Predictability, especially in high-reliability industries, often outweighs raw speed.

Perhaps the most underestimated economic benefit of Secondary Drilling is yield stabilization.

Misaligned holes directly contribute to:

Annular ring breakout

Uneven copper plating thickness

Via barrel stress concentration

Increased electrical resistance variability

By correcting positional errors before metallization, Secondary Drilling improves first-pass yield, reduces scrap rates, and minimizes rework loops.

In high-layer-count boards, even a 2–3% yield improvement can fully offset the added cost of Secondary Drilling. This is why advanced PCB manufacturers rarely debate whether Secondary Drilling is “worth it”; they focus instead on where it delivers the highest return.

At the mechanical level, hole position accuracy directly affects via integrity.

When a drilled hole deviates from the pad center:

Copper thickness becomes uneven around the via circumference

Stress concentrates on thinner regions during thermal cycling

Crack initiation probability increases

Secondary-Drilling restores concentricity between the hole wall and inner-layer pads, producing uniform copper distribution after plating.

In my assessment, many so-called “plating failures” are actually mechanical alignment failures in disguise. Secondary -Drilling addresses the root cause rather than treating the symptom.

Electrical performance is increasingly sensitive to geometric precision.

In high-speed digital and RF designs:

Via impedance is affected by hole diameter and pad alignment

Skew and reflection increase with structural asymmetry

Crosstalk worsens when reference geometries are inconsistent

By ensuring micron-level hole positioning, Secondary-Drilling contributes to repeatable electrical behavior across large panel arrays.

While simulation tools often assume perfect via geometry, real-world manufacturing rarely achieves it without correction. Secondary Drilling is one of the few processes that actively bridges this gap between simulation and reality.

Thermal cycling reliability is not solely determined by material selection. Geometry plays an equally critical role.

Misaligned vias experience:

Non-uniform expansion stress

Accelerated copper fatigue

Increased risk of barrel cracking

Secondary-Drilling improves stress symmetry, which in turn enhances thermal endurance over thousands of cycles. This effect is subtle but cumulative—exactly the type of reliability improvement that only becomes visible in long-term field data.

One of the strongest arguments in favor of Secondary Drilling is consistency.

Without it, hole positioning accuracy depends heavily on:

Lamination variability

Copper density distribution

Environmental fluctuations

Secondary-Drilling decouples final accuracy from these variables by applying a measurement-driven correction step. As a result, panel-to-panel and batch-to-batch variation is significantly reduced.

From a system reliability perspective, consistency is often more valuable than peak performance.

One of the most common misconceptions surrounding Secondary-Drilling is that it is purely a manufacturing-side decision. In reality, its effectiveness and cost-efficiency are largely determined during PCB design.

Design choices that significantly influence the necessity of Secondary Drilling include:

Layer count and symmetry

Copper distribution balance

Pad size relative to drill diameter

Aspect ratio of vias

Tolerance stack-up across inner layers

When designers assume ideal layer registration without accounting for lamination distortion, Secondary Drilling becomes a reactive correction. When distortion risk is anticipated early, Secondary Drilling becomes a controlled precision strategy.

From my perspective, the earlier Secondary Drilling is acknowledged in the design–manufacturing dialogue, the less intrusive and costly it becomes.

Certain PCB architectures inherently amplify positional risk and therefore benefit disproportionately from Secondary Drilling.

These include:

Ultra-high layer count boards (≥24 layers)

Mixed material stack-ups (e.g., FR-4 combined with low-Dk materials)

Uneven copper plane distribution

Fine annular ring designs approaching minimum IPC limits

Backplane and daughtercard interconnect regions

In these cases, the cumulative distortion introduced by lamination and thermal cycling exceeds what primary drilling alone can reliably compensate.

Secondary-Drilling, applied selectively to high-risk hole groups, restores alignment without forcing designers to compromise routing density or pad geometry.

Despite its advantages, Secondary Drilling is not universally beneficial. Overuse can introduce unnecessary complexity and cost.

Situations where Secondary Drilling may be avoided include:

Low-layer-count boards with symmetrical stack-ups

Designs with generous annular ring allowances

Products with low reliability or lifecycle demands

Applications where positional tolerance is non-critical

In such cases, robust primary drilling and lamination control may achieve sufficient accuracy. Applying Secondary Drilling here would yield diminishing returns.

This distinction is critical: Secondary Drilling is a precision amplifier, not a universal solution.

In my experience, the biggest obstacle to effective Secondary-Drilling is not technical capability but communication failure.

Common issues include:

Designers unaware of lamination distortion behavior

Manufacturers not informed of critical hole prioritization

Procurement teams focusing solely on per-unit cost

Late-stage design changes that disrupt drilling strategy

When Secondary-Drilling is introduced without shared understanding, it often fails to deliver its full value.

Conversely, when designers, CAM engineers, and process engineers collaborate early, Secondary Drilling becomes predictable, repeatable, and economically rational.

Micron-level hole positioning accuracy has become one of the most decisive factors in modern PCB manufacturing. As layer counts increase, materials diversify, and performance margins narrow, mechanical precision is no longer a secondary concern—it is a foundational requirement.

Throughout this analysis, Secondary Drilling has been examined not simply as an additional manufacturing step, but as a precision correction philosophy. It acknowledges the unavoidable reality of material movement, lamination distortion, and thermal stress, and responds with a targeted, measurement-driven solution rather than relying solely on upstream prediction.

From a cost perspective, its value lies not in reducing visible expenses, but in redistributing risk—from unpredictable yield loss and long-term reliability issues to controlled, intentional process investment. From a performance standpoint, its influence extends beyond mechanical alignment into electrical consistency, thermal endurance, and lifecycle stability.

Most importantly, Secondary Drilling highlights a broader truth about advanced PCB manufacturing: true precision is rarely achieved by a single process. It emerges from collaboration between design intent and manufacturing reality, supported by corrective mechanisms that respect physical limits.

In my view, the growing relevance of Secondary Drilling reflects the industry’s maturity. It signals a shift away from idealized assumptions toward honest, data-driven correction—an approach that will remain essential as PCB technology continues to push toward ever-smaller tolerances.

It is most commonly applied in high-layer-count boards, HDI designs, fine-pitch BGA interconnects, RF and high-speed digital PCBs, and electronics used in aerospace, medical, and automotive safety systems—where positional accuracy directly affects performance and reliability.

As the number of layers increases, small positional deviations accumulate across the stack-up. Misaligned holes can lead to annular ring reduction, uneven plating thickness, and increased mechanical stress on vias. In high-layer-count PCBs, even micron-level errors can significantly impact yield and long-term reliability.

Improving primary drilling focuses on preventing errors through tighter process control and better equipment. Secondary Drilling, by contrast, addresses deviations that occur despite these controls. It is a corrective step based on actual material behavior after lamination, making it especially effective for managing unavoidable distortion.

While it introduces additional processing steps, Secondary Drilling does not always increase total manufacturing cost. In many high-density or high-reliability designs, the improvement in yield, reduction in rework, and prevention of field failures can outweigh the added process expense.

Simulation tools and digital twins significantly improve prediction accuracy, but they cannot fully eliminate real-world material variability. Factors such as resin flow, copper imbalance, and thermal contraction still introduce deviations. Secondary Drilling complements simulation by correcting these deviations based on measured results rather than theoretical models.

Connect to a Jerico Multilayer PCB engineer to support your project!

Request A Quote